Lab 01 - Introduction to the

spatstat package

Background

A spatial point pattern is a dataset comprised of the locations of ‘things’ or ‘events’. This might be the locations of trees in a forest, road traffic accidents, crimes, incidents of diseases, etc… For these data, the spatial arrangement of the points is the focus of investigation. Depending on your analytical aims, this might be a description of spatial trends in the density of points, relationships with covariates, or so on. The analysis of point patterns can provide key evidence in many fields of research (e.g., ecology, epidemiology, geoscience, astronomy, crime research, cell biology, econometrics).

In this lab we will:

- Learn how to import point data into the

spatstatpackage. - Learn how to add marks to a point pattern and estimate the observation window.

- Explore ways to visualise point patterns and images.

- Learn how to extract and modify the information contained in

pppobjects.

Importing point data into spatstat

At its simplest, a spatial point dataset is comprised of the

locations of ‘things’ or ‘events’ (i.e., a series of x and y

coordinates). In spatstat, these data are stored in an

object of class ppp (i.e., a planar point pattern). Before

the analytical tools available within the spatstat package

can be used, point data need to first be imported and converted into a

ppp object.

Assuming you have already installed the spatstat

package, the first step of any analysis is to import the package and

dataset(s). Here we will work with point data on synaptic vesicles

observed in rat brain tissue. These data were used to support work by

Khanmohammadi et al. (2014).

These data are part of the spatstat package, and stored

as a .txt file in a folder that is generated when the package is

installed. We could have loaded these data by calling

data(vesicles), but the process described below mimics a

more realistic workflow where you would be importing data stored locally

on your computer.

#load the spatstat package

library(spatstat)

#Define the file path to the dataset

path <- system.file("rawdata/vesicles/vesicles.txt", package = "spatstat.data")

#Import the vesicles dataset

vesicles <- read.table(path,

header = TRUE)

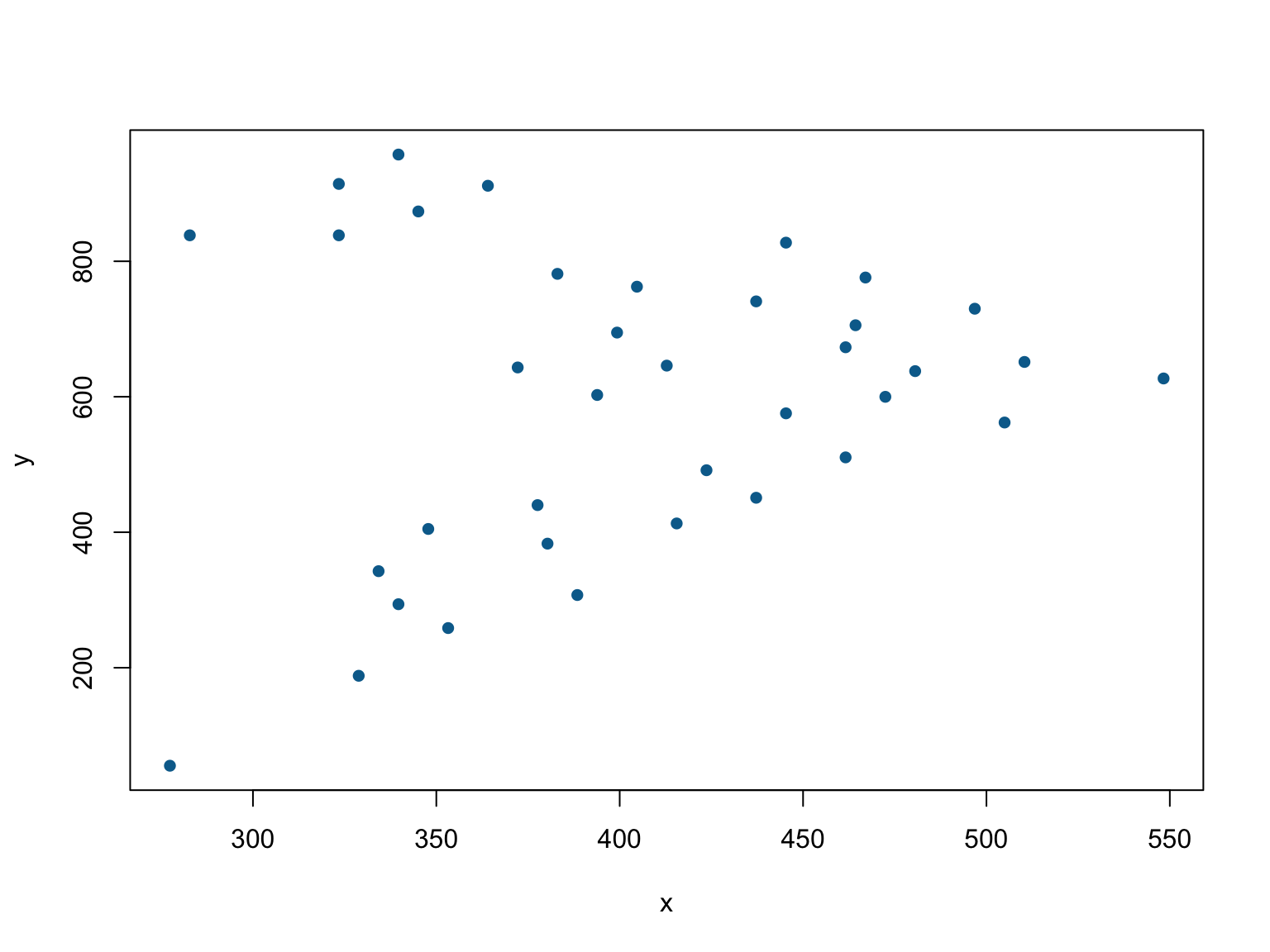

#Visualise the data

plot(y ~ x,

pch = 16,

col = "#046C9A",

data = vesicles)

Importing point data into R is fairly straightforward

and similar to many other workflows, but, unlike with other packages,

converting these data to a ppp object requires additional

information on the sampling window. There are several ways to do this,

but we will explore an option based on importing information on the

coordinates of a ‘bounding box’. This approach assumes you have

information on the coordinates defining the edge of a sampling window

stored in a data file (e.g., a .txt or .csv file) . The process is

fairly straightforward and involves importing the coordinates and

converting them to an owin object using the

owin() function. Depending on the complexity of the window,

this may involve converting a dataset into a list, as shown in the

example below.

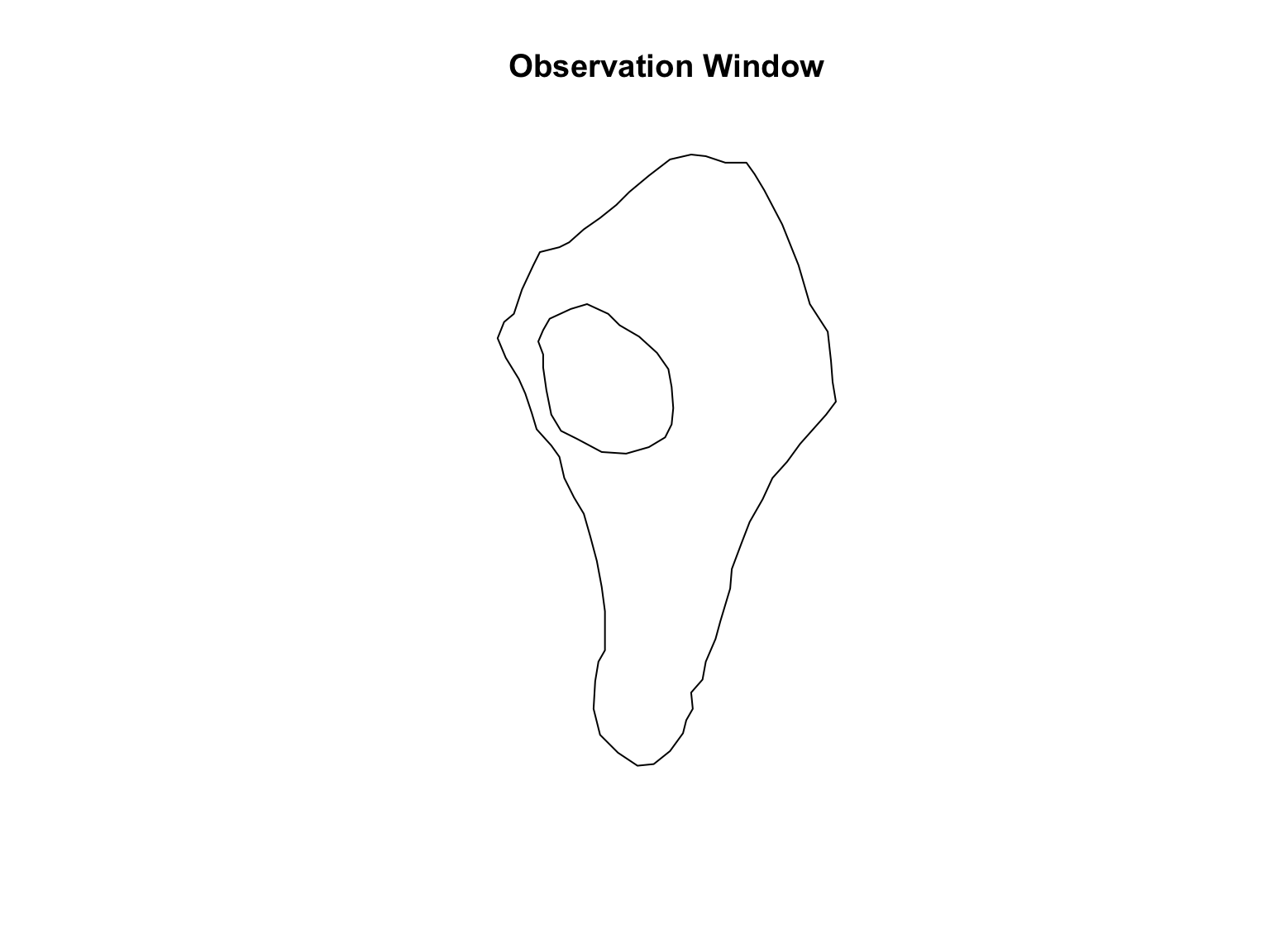

# Import the locations of the

path <- system.file("rawdata/vesicles/vesicleswindow.txt", package = "spatstat.data")

ves_win <- read.table(path,

header = TRUE)

# Convert to a list with each element containing information on each "piece"

# This is because there is a hole in the window.

ves_win_stack <- list()

ves_win_stack[[1]] <- ves_win[which(ves_win$id == 1),]

ves_win_stack[[2]] <- ves_win[which(ves_win$id == 2),]

#Convert the list to an owin object

ves_win <- owin(poly = ves_win_stack)

#Visualise the window

plot(ves_win,

main = "Observation Window")

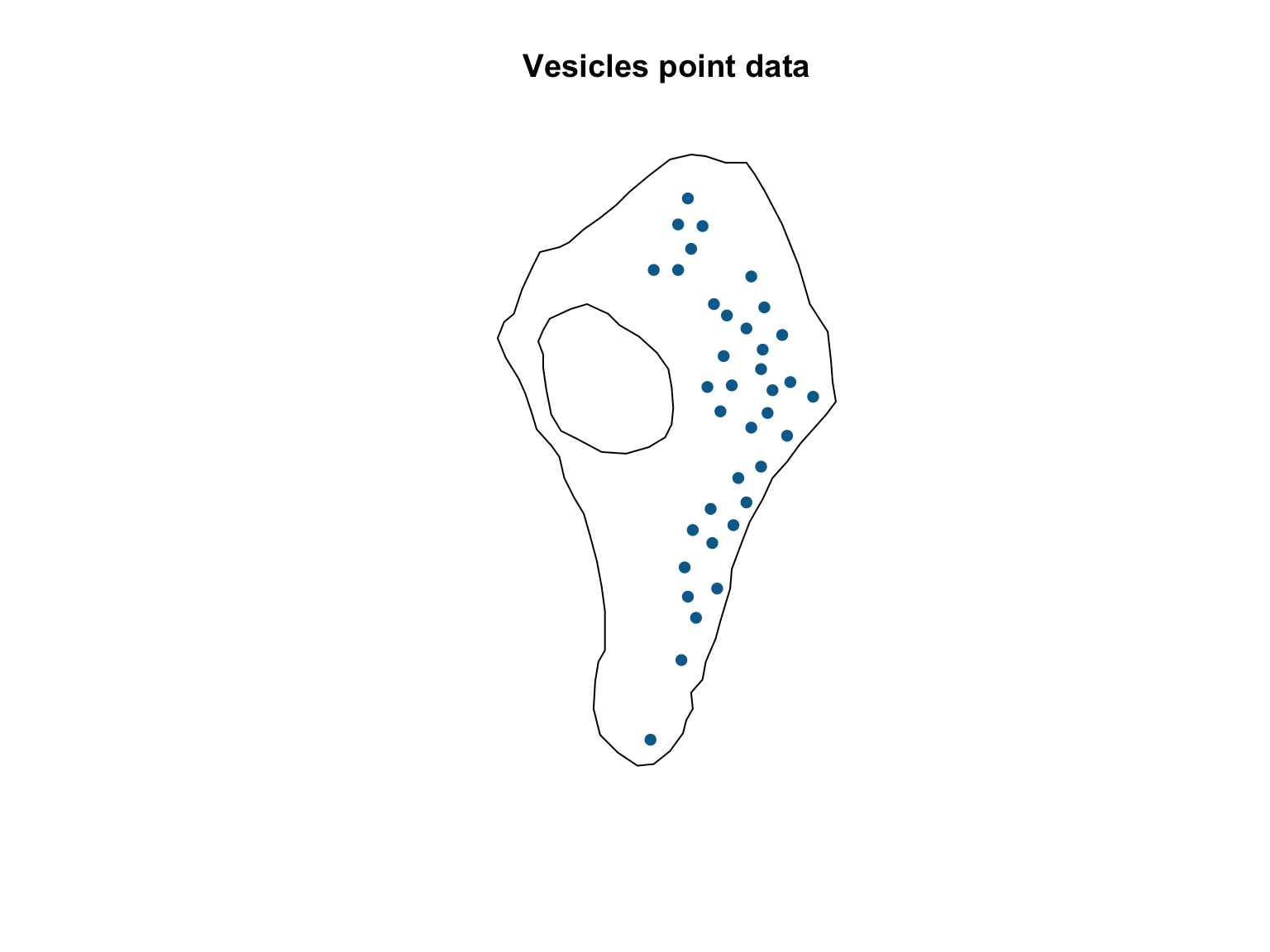

Once the window is defined, converting a dataset into a

ppp object is relatively straighforward and involves the

ppp() function.

#Convert to a ppp object

vesicles_ppp <- ppp(x = vesicles$x, # X coordinates

y = vesicles$y, # Y coordinates

window = ves_win) # Observation window

#Visualise the dataset

plot(vesicles_ppp,

pch = 16,

cols = "#046C9A",

main = "Vesicles point data")

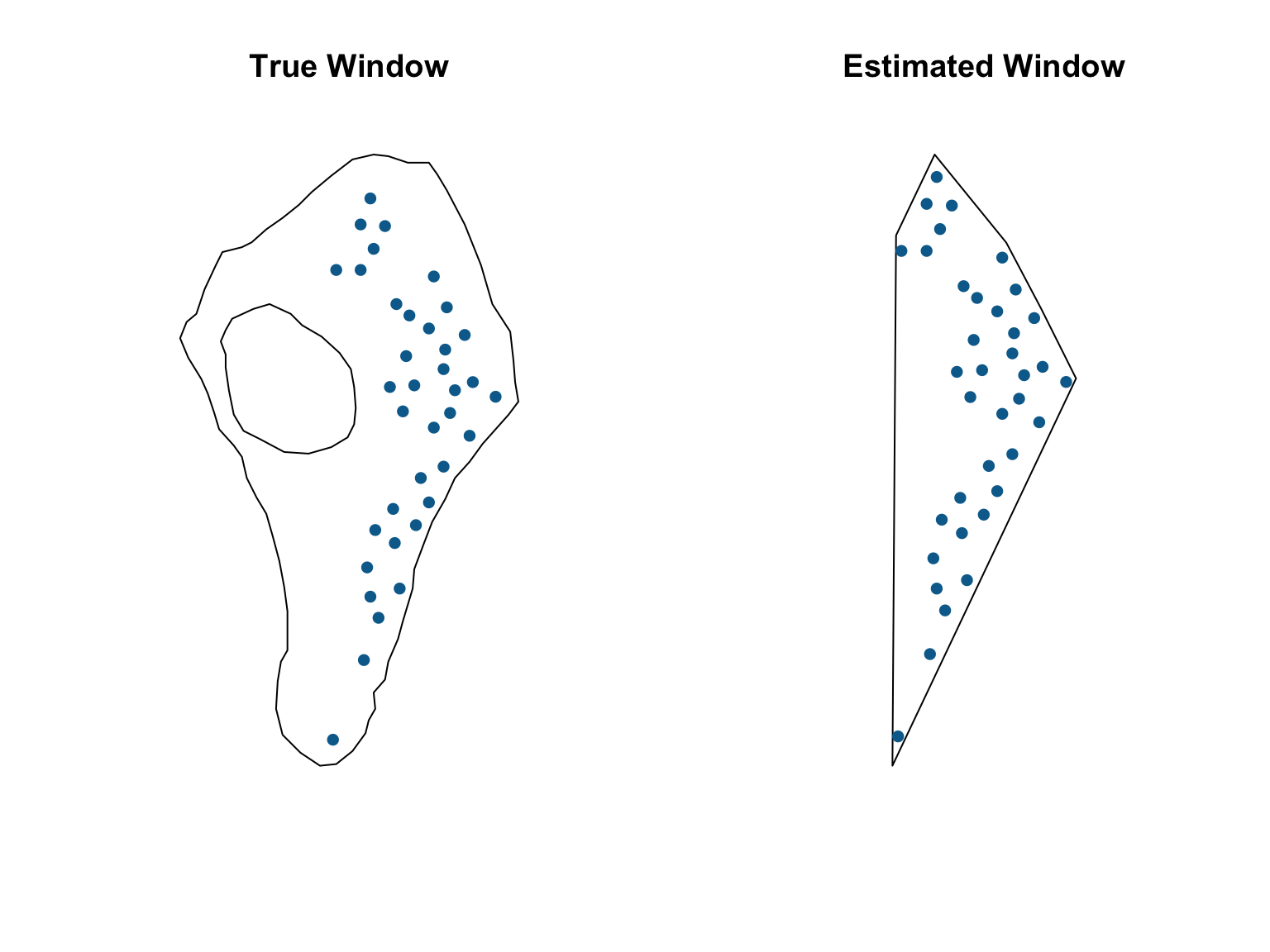

Estimating the window

If you only had point data and no information on the window, the

spatstat package has methods for estimating the observation

window. One option is to use the ripras() function, which

computes the Ripley-Rasson estimate of the spatial domain from which a

particular set of data came.

#Estimate the sampling window

est_win <- ripras(x = vesicles$x, y = vesicles$y)

#Convert to a ppp object

vesicles_ppp_2 <- ppp(x = vesicles$x, # X coordinates

y = vesicles$y, # Y coordinates

window = est_win) # Observation window

#Visualise the two datasets

par(mfrow = c(1,2))

plot(vesicles_ppp,

pch = 16,

cols = "#046C9A",

main = "True Window")

plot(vesicles_ppp_2,

pch = 16,

cols = "#046C9A",

main = "Estimated Window")

While this approach can serve as a reasonable solution for situations when the window is unknown, it risks biasing any downstream estimates, and any resulting inference should be approached with caution.

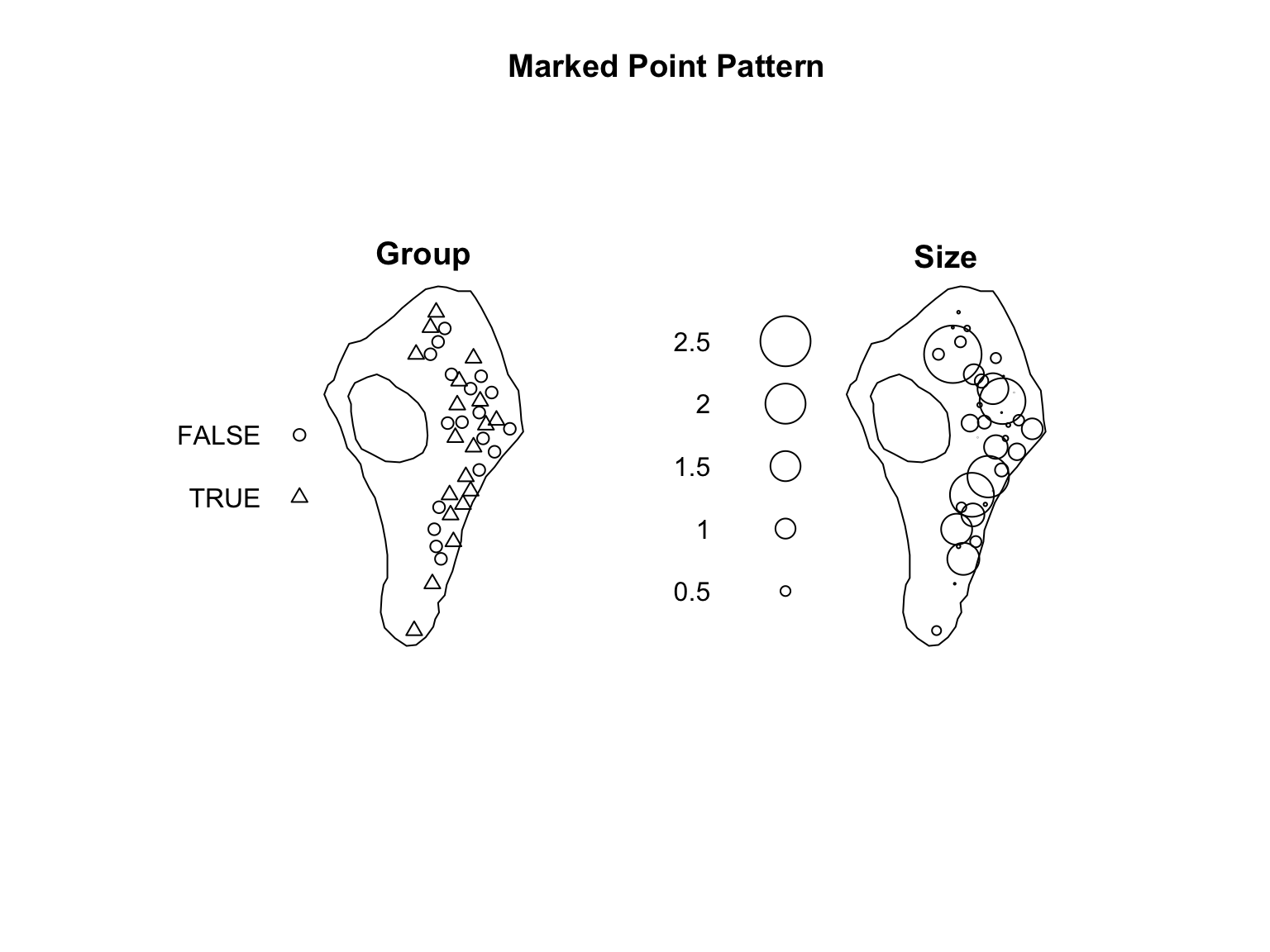

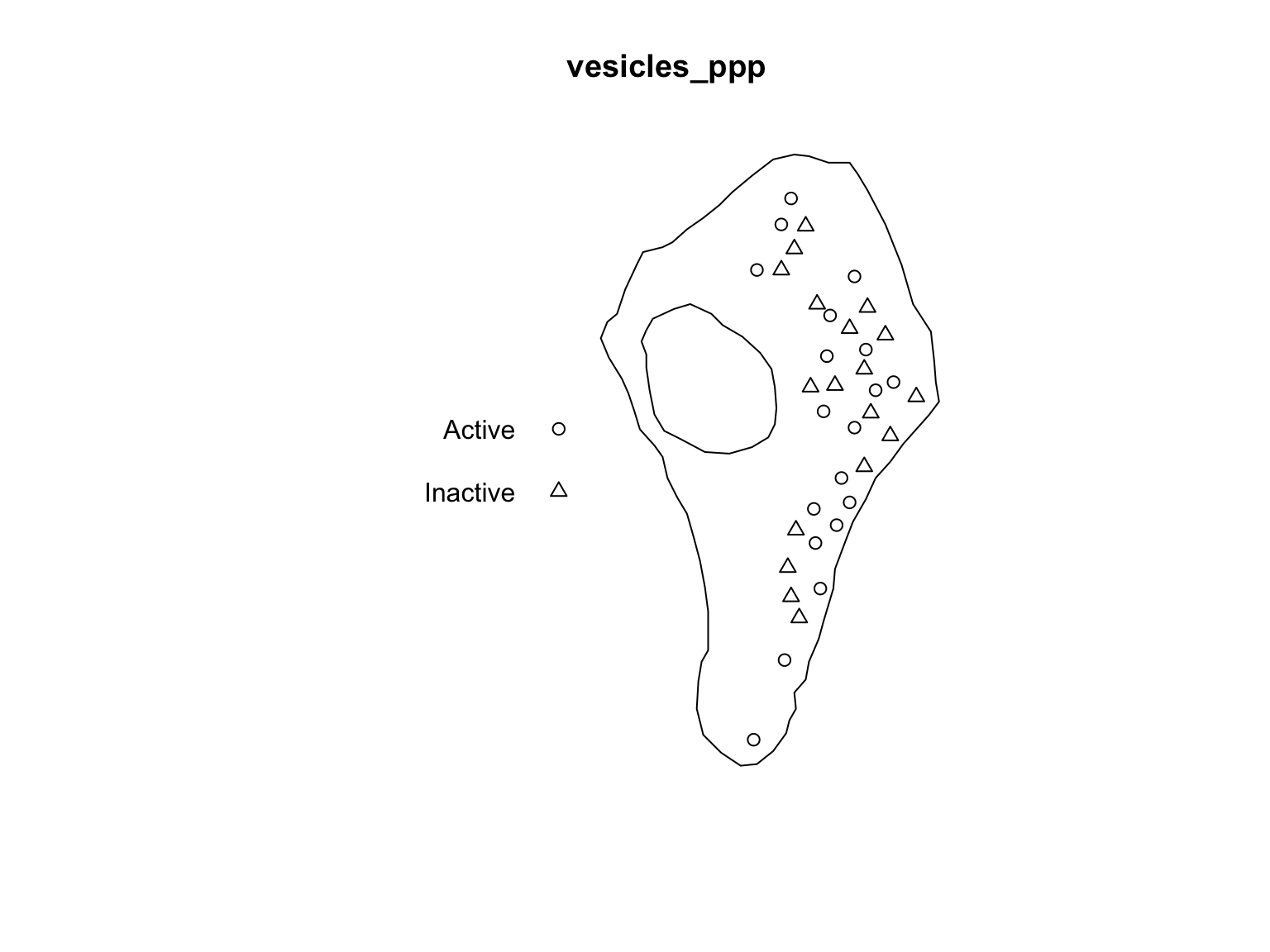

Marked point patterns

Sometimes we have points of several types, or a marked point pattern (i.e., auxiliary information). While the original vesicles dataset does not contain any ‘marks’ we can easily add some randomly generated supporting information for demonstration purposes.

#Randomly assign a "group"

group <- as.logical(rbinom(n = nrow(vesicles), size = 1, p = 0.5))

#Randomly define a "size"

size <- rgamma(n = nrow(vesicles), shape = 1)

#Assign the supporting information to the point pattern

marks(vesicles_ppp) <- data.frame(Group = group,

Size = size)

#Visualise the result

plot(vesicles_ppp,

main = "Marked Point Pattern")

Inspecting and Exploring data

Plotting methods

Plotting a point pattern

As shown above, running plot on spatstat objects will

generate simple plots of point pattern datasets and features (e.g.,

marks, windows, etc.). Effective plots of spatial data are critical for

communication, and typically requires bespoke modifications of standard,

default plotting methods. We will explore some of these options

here.

The default plot method for ppp objects

displays the observation window, the points, as well as information on

all marks associated with the dataset. For information see

help("plot.ppp"). The defaults are useful for a quick,

‘on-the-fly’ visualisation, but are rarely useful for scientific

communication. Depending on your needs there is a lot of flexibility in

how these figures can be made to look.

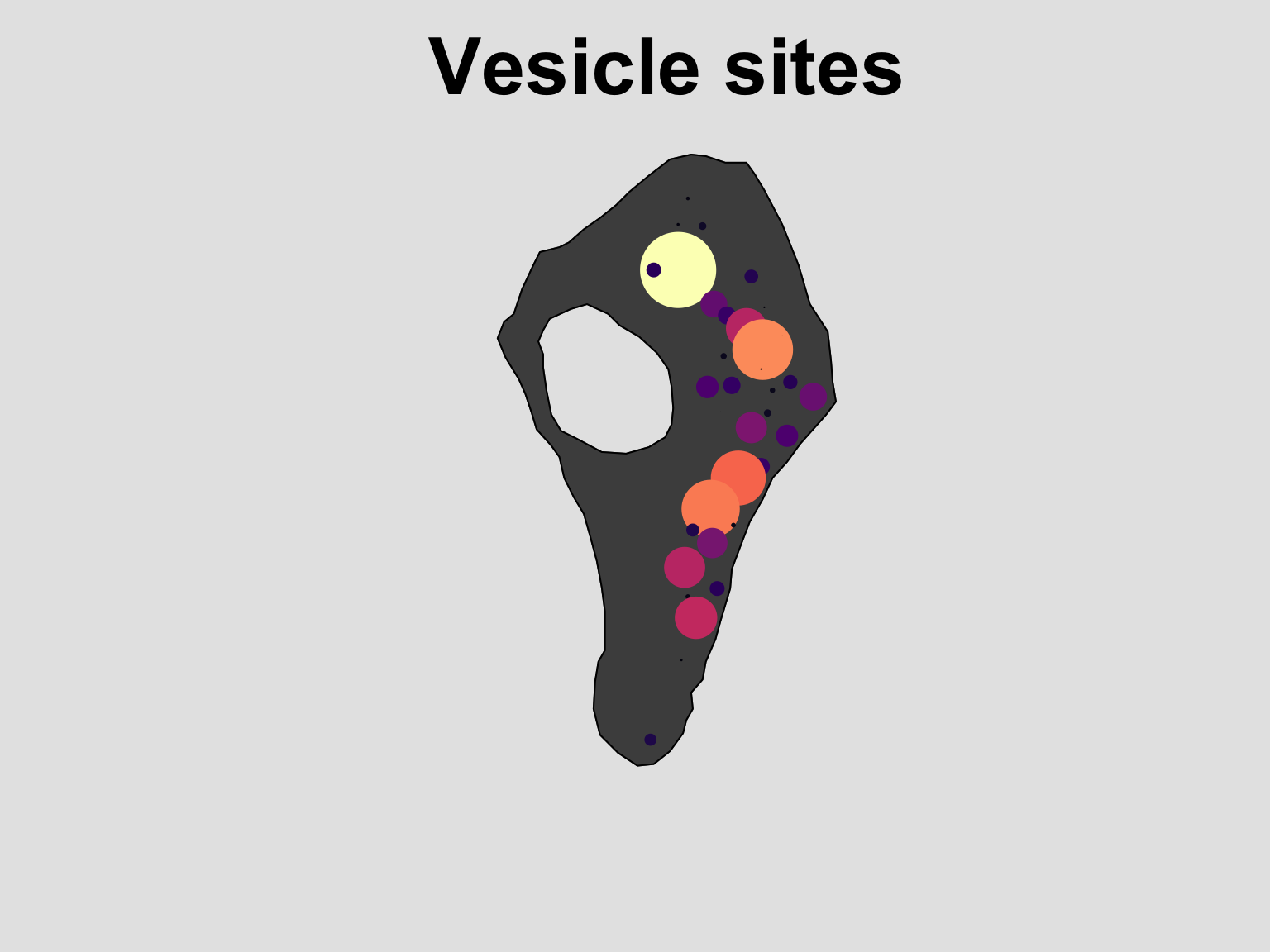

library(viridis)

#Define a colour pallet to use

col_pal <- colourmap(magma(128), range = range(size))

#Refine the figure

plot(vesicles_ppp, # The dataset to visualise

which.marks = "Size", # Which mark to use

col = "grey30", #The colour of the window

cols = col_pal, #The colours of the points

pch = 16, # The plotting symbol

main = "Vesicle sites", # The title

par(bg="grey90", cex.main = 3), # Flexible modification of the graphical parameters

legend = F) # Turn of the legend depending on needs

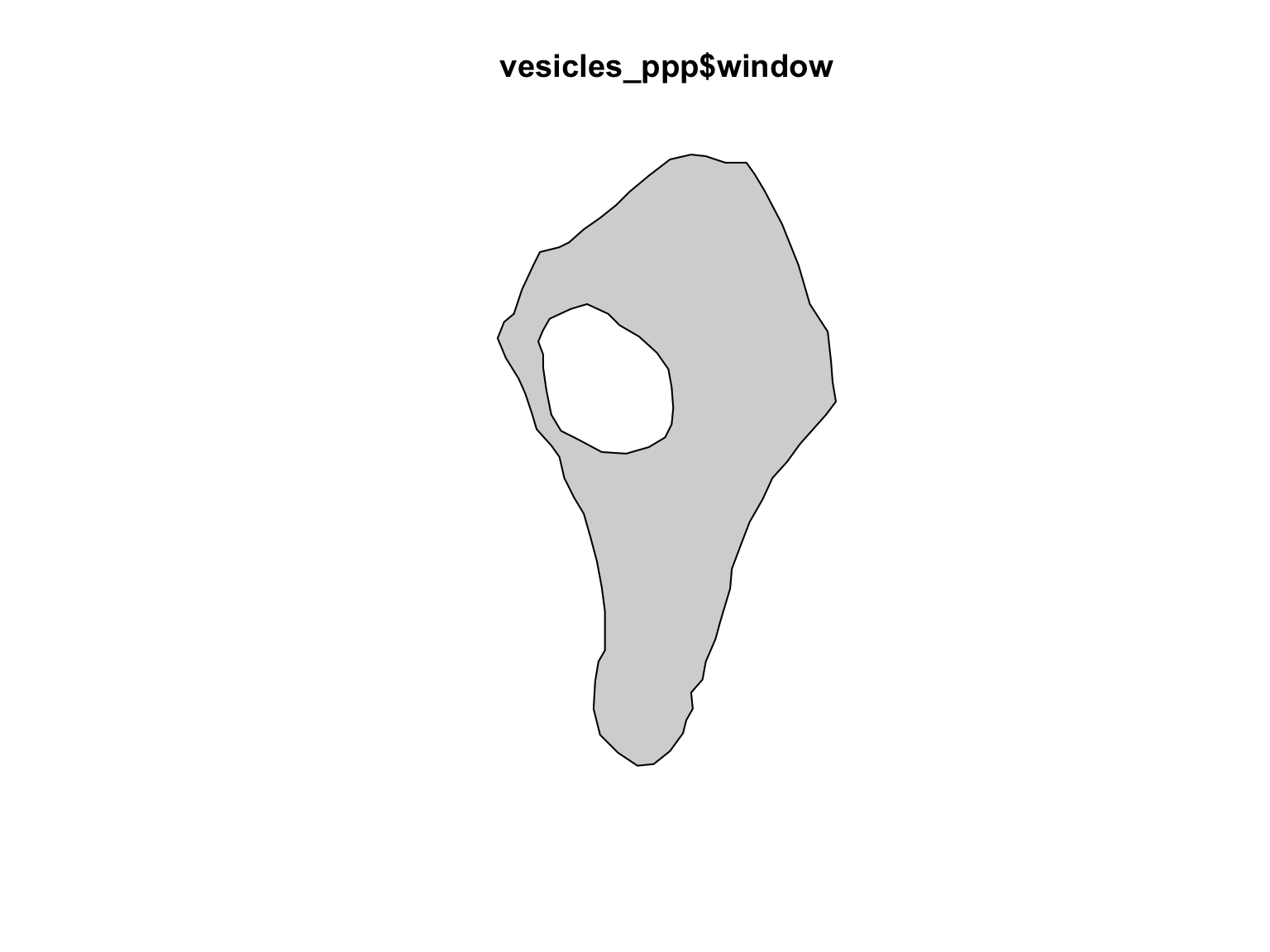

Plotting a window

In some cases we might be interested in the window alone. This can be

done by extracting the window from the ppp object.

plot(vesicles_ppp$window,

col = rgb(0,0,0,0.2))

The above plot is simple, but it can be modified as needed. See

help("plot.owin") for details.

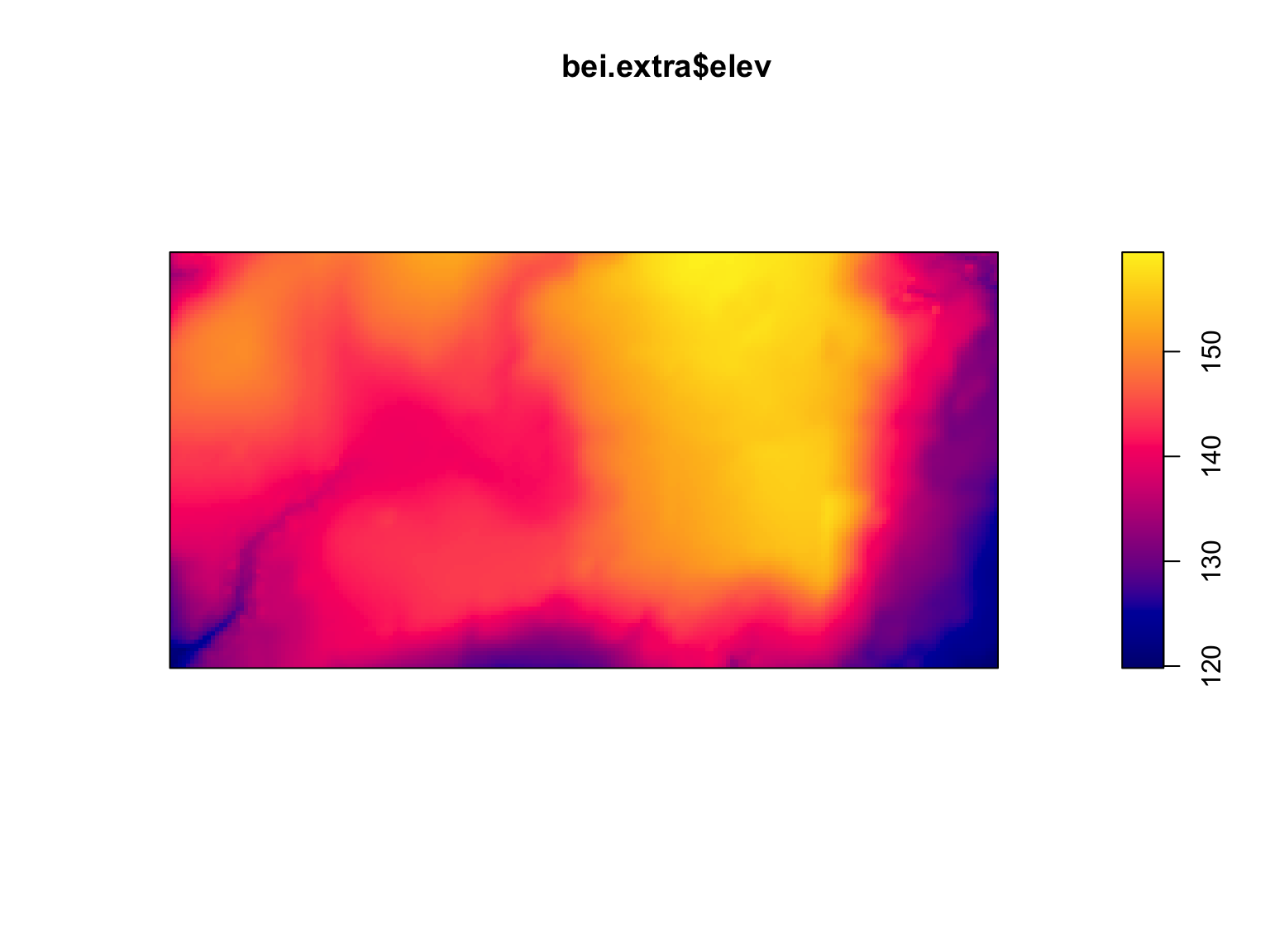

Plotting an image

Sometimes a point pattern will be accompanied by a continuously

varying co-variate. In spatstat these covariates are

imported as ‘images’. Depending on the information contained in these

covariates, they can be visualised in two, or three dimensions. By

default, the 3 dimensional perspective plots can be challenging to

interpret, but they are very flexible and can produce high quality

images (see: help("persp")). The default plotting methods

for 2 dimensional plots of images are redily interpretable, so we will

not explore them in detail here. If you want to modify them, see

help("plot.im").

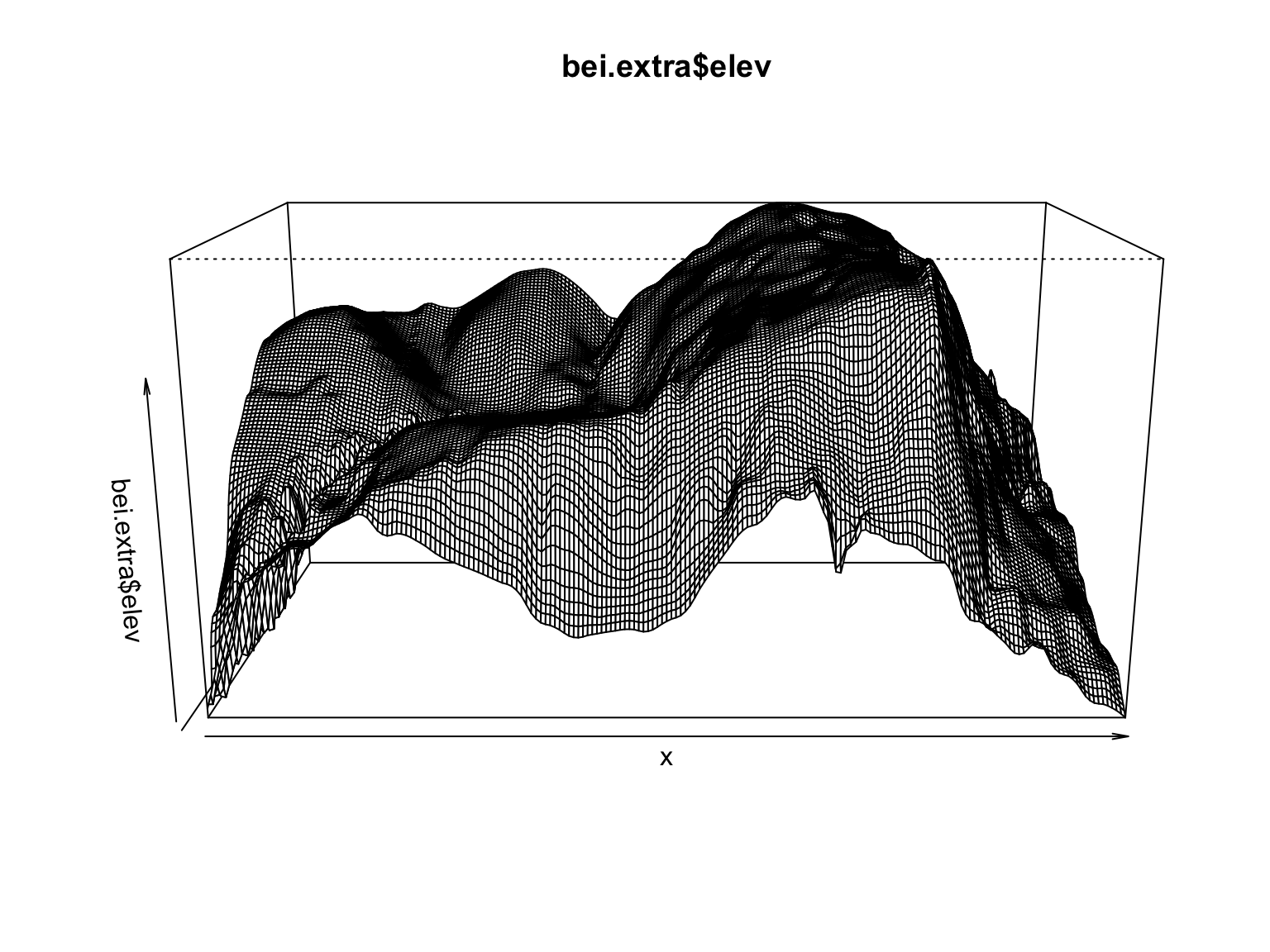

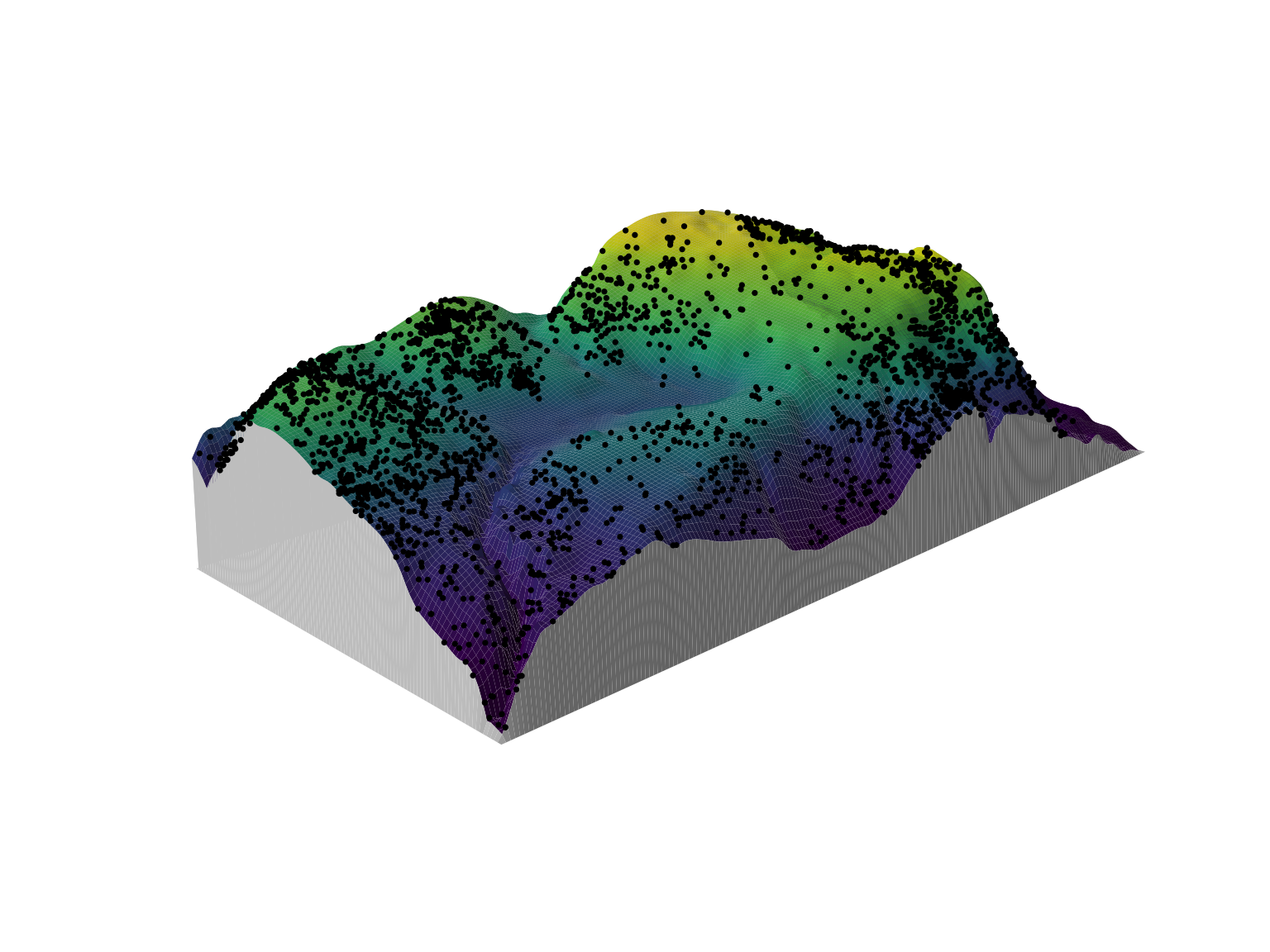

To demonstrate how to visualise images, we will use the

bei dataset. This is a point pattern giving the locations

of 3605 trees in a tropical rain forest in Panama. Accompanied by

covariate data giving the elevation (altitude) and slope of elevation in

the study region. The supporting information is stored in an object

called bei.extra.

#Load in the data

data("bei")

plot(bei.extra$elev)

persp(bei.extra$elev)

fig <- persp(bei.extra$elev, # source data

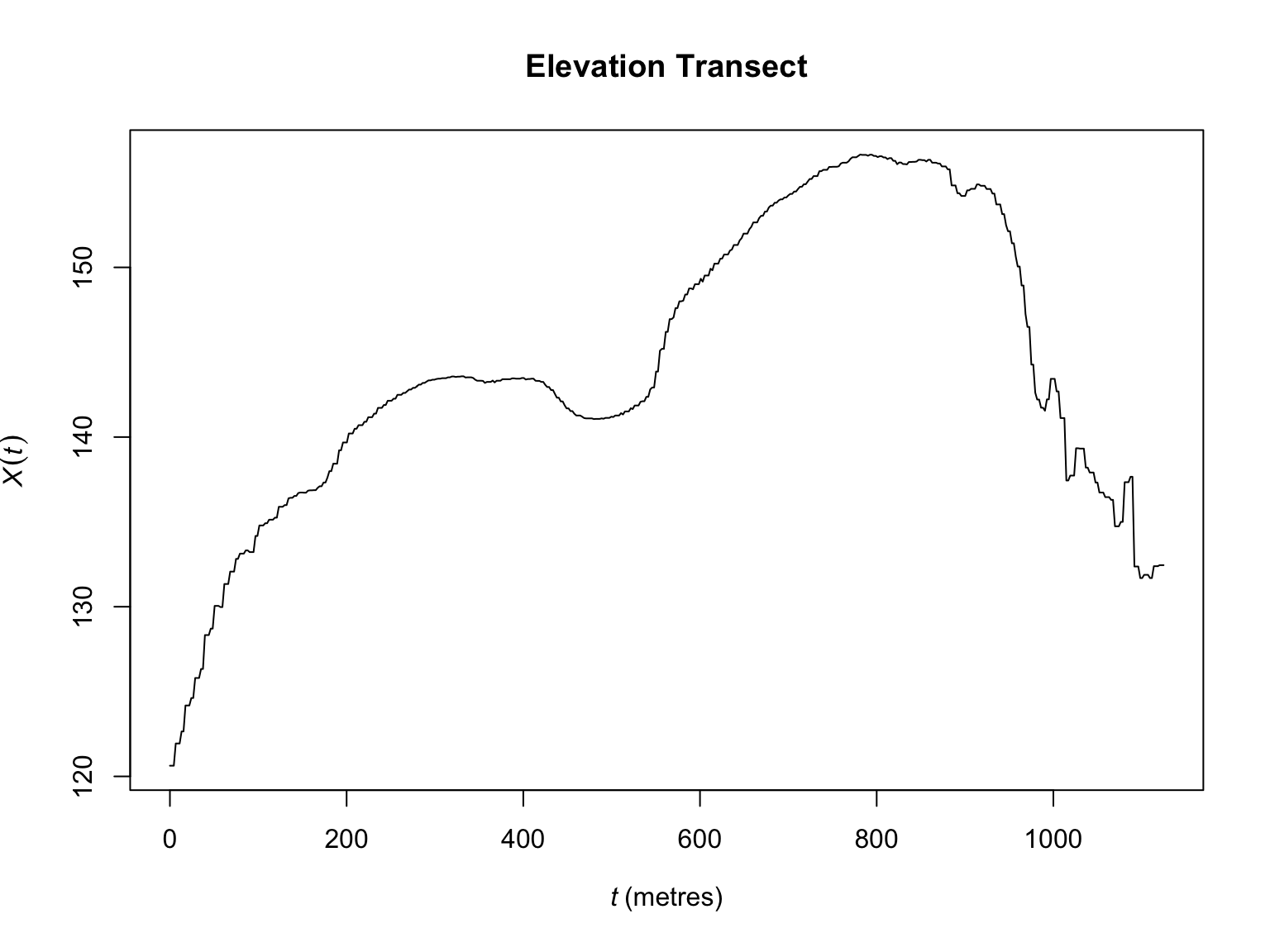

theta = -45, phi = 18, # rotation

expand = 7, # z-axis expansion

border = NA, #remove grid borders

apron = TRUE, #apron around edge

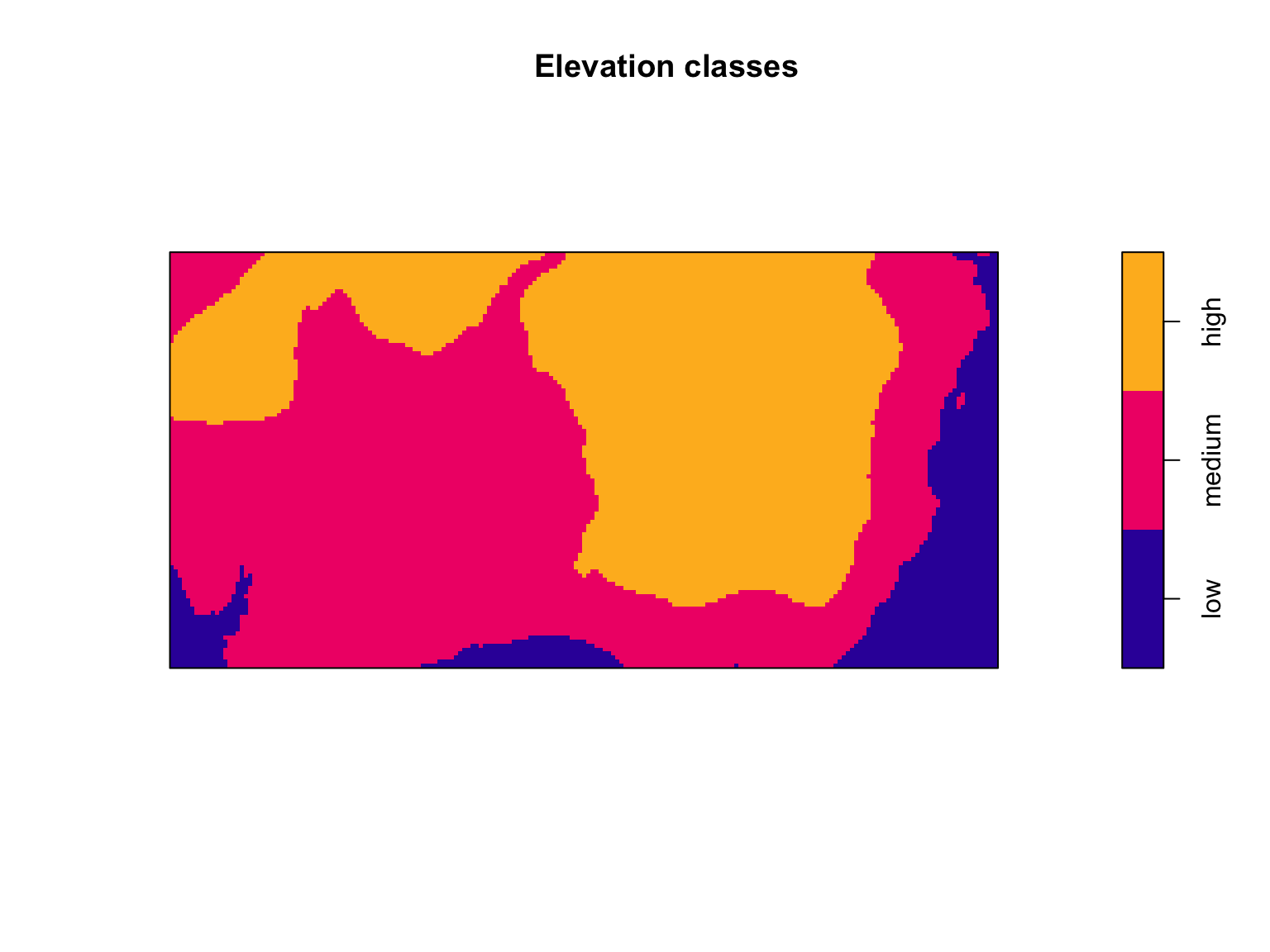

shade = 0.3, # shading

box = FALSE, # axes on/off

main = "", # title

visible = TRUE, #Supporting calculations

colmap = viridis(200) ) # colour pallet

perspPoints(bei, Z = bei.extra$elev, M = fig, pch = 16, cex = 0.5)

The extra step of setting visible = TRUE is required for

overlaying the locations of points on top of a perspective plot. This

determines which portions of the plot are actually visible, and is then

passed on to the M argument in plot.im.

Sometimes you might be interested in visualising a transect of the

values of a supporting covariate across the sampling window. This can be

useful way of seeing some of the spatial structure in a covariate. This

can be achieved via the transect.im() function. Note: by

default the transect goes from the bottom left of an image, to the top

right, but this can be modified as needed.

plot(transect.im(bei.extra$elev),

main = "Elevation Transect")

Other times you might be interested in dividing a continuously

varying image into discrete bins. The cut.im() function is

a flexible tool for turning a numeric image into a factor-based image.

The bin widths are even by default, but can be manually defined to suit

your needs.

plot(cut(bei.extra$elev,

3,

labels = c("low","medium","high")),

main = "Elevation classes")

The data contained in images can also be passed along to other functions as needed.

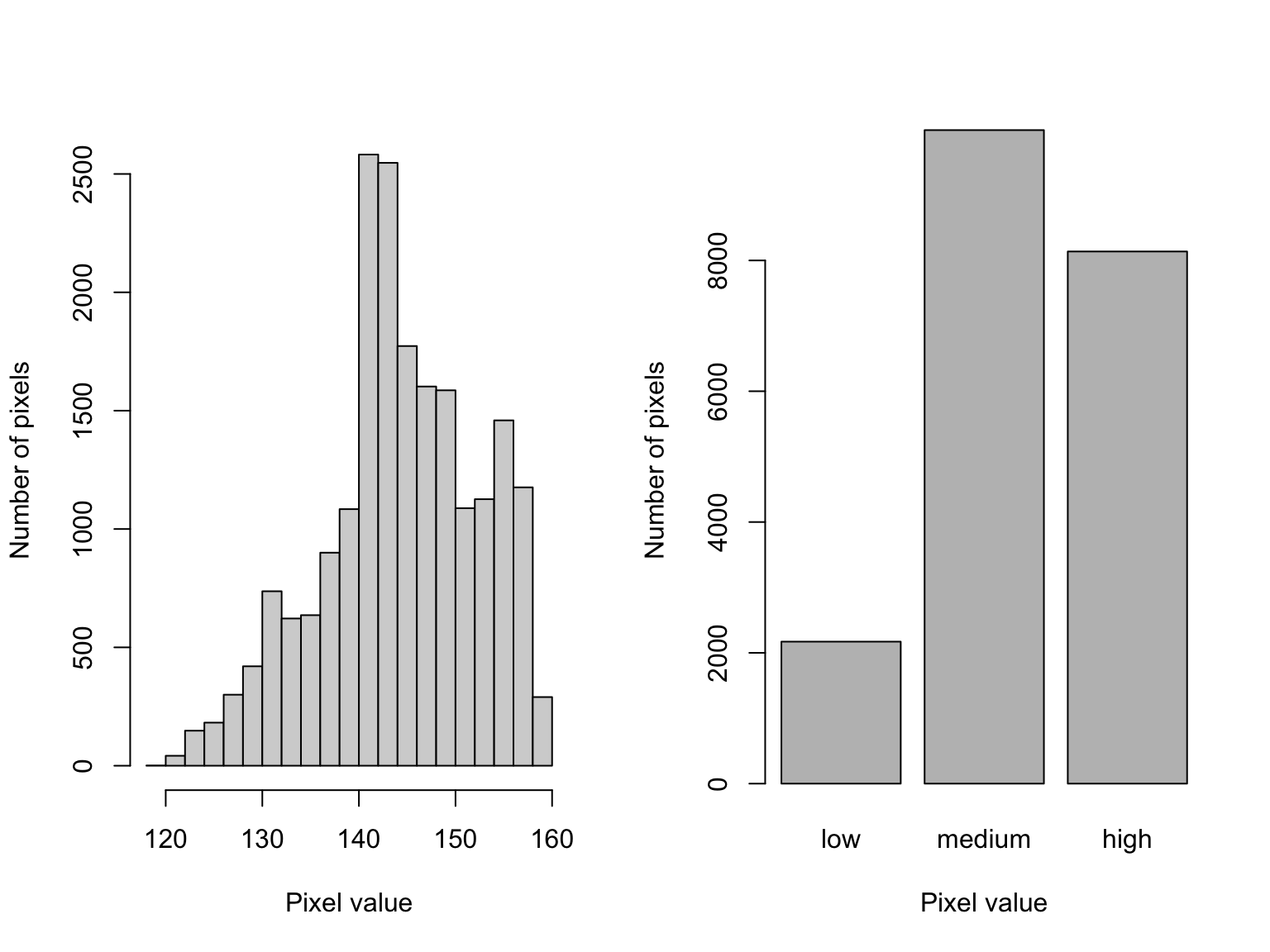

par(mfrow = c(1,2))

hist(bei.extra$elev, main = "")

hist(cut(bei.extra$elev,

3,

labels = c("low","medium","high")),

main = "")

Working with point patterns

Extracting information from ppp objects

The spatstat package has a number of functions for

extracting basic information from a point pattern. Some of the more

useful ones are described below

#Basic summary information

summary(vesicles_ppp)## Marked planar point pattern: 37 points

## Average intensity 0.0001336176 points per square unit

##

## Coordinates are given to 5 decimal places

##

## Mark variables: Group, Size

## Summary:

## Group Size

## Mode :logical Min. :0.009485

## FALSE:18 1st Qu.:0.182279

## TRUE :19 Median :0.550348

## Mean :0.748652

## 3rd Qu.:1.041947

## Max. :2.864741

##

## Window: polygonal boundary

## 2 separate polygons (1 hole)

## vertices area relative.area

## polygon 1 69 317963.0 1.150

## polygon 2 (hole) 23 -41052.9 -0.148

## enclosing rectangle: [22.6796, 586.2292] x [11.9756, 1030.7] units

## (563.5 x 1019 units)

## Window area = 276910 square units

## Fraction of frame area: 0.482#Number of points

npoints(vesicles_ppp)## [1] 37#marks

head(marks(vesicles_ppp))## Group Size

## 1 FALSE 0.0687878

## 2 TRUE 0.5178509

## 3 FALSE 0.2893958

## 4 TRUE 0.1160360

## 5 TRUE 0.1408090

## 6 FALSE 0.5503479#coordinates

head(coords(vesicles_ppp))## x y

## 1 467.0168 776.0189

## 2 445.3418 827.4970

## 3 364.0606 911.4876

## 4 323.4200 914.1969

## 5 339.6762 957.5469

## 6 345.0950 873.5563#Coordinates and mark information

head(as.data.frame(vesicles_ppp))## x y Group Size

## 1 467.0168 776.0189 FALSE 0.0687878

## 2 445.3418 827.4970 TRUE 0.5178509

## 3 364.0606 911.4876 FALSE 0.2893958

## 4 323.4200 914.1969 TRUE 0.1160360

## 5 339.6762 957.5469 TRUE 0.1408090

## 6 345.0950 873.5563 FALSE 0.5503479These functions can also be paired with the assign operator

<- to modify components of a ppp object as

needed. For instance, change the TRUE/FALSE

group labels can be done as follows:

#Store the marks

m <- marks(vesicles_ppp)

#Rename as needed

m$Group[which(m$Group == TRUE)] <- "Active"

m$Group[which(m$Group == FALSE)] <- "Inactive"

marks(vesicles_ppp) <- m

head(marks(vesicles_ppp))## Group Size

## 1 Inactive 0.0687878

## 2 Active 0.5178509

## 3 Inactive 0.2893958

## 4 Active 0.1160360

## 5 Active 0.1408090

## 6 Inactive 0.5503479plot(vesicles_ppp, which.marks = "Group")

This is particularly useful if we calculate values midway through an

analyses and would like to append them to our ppp object.

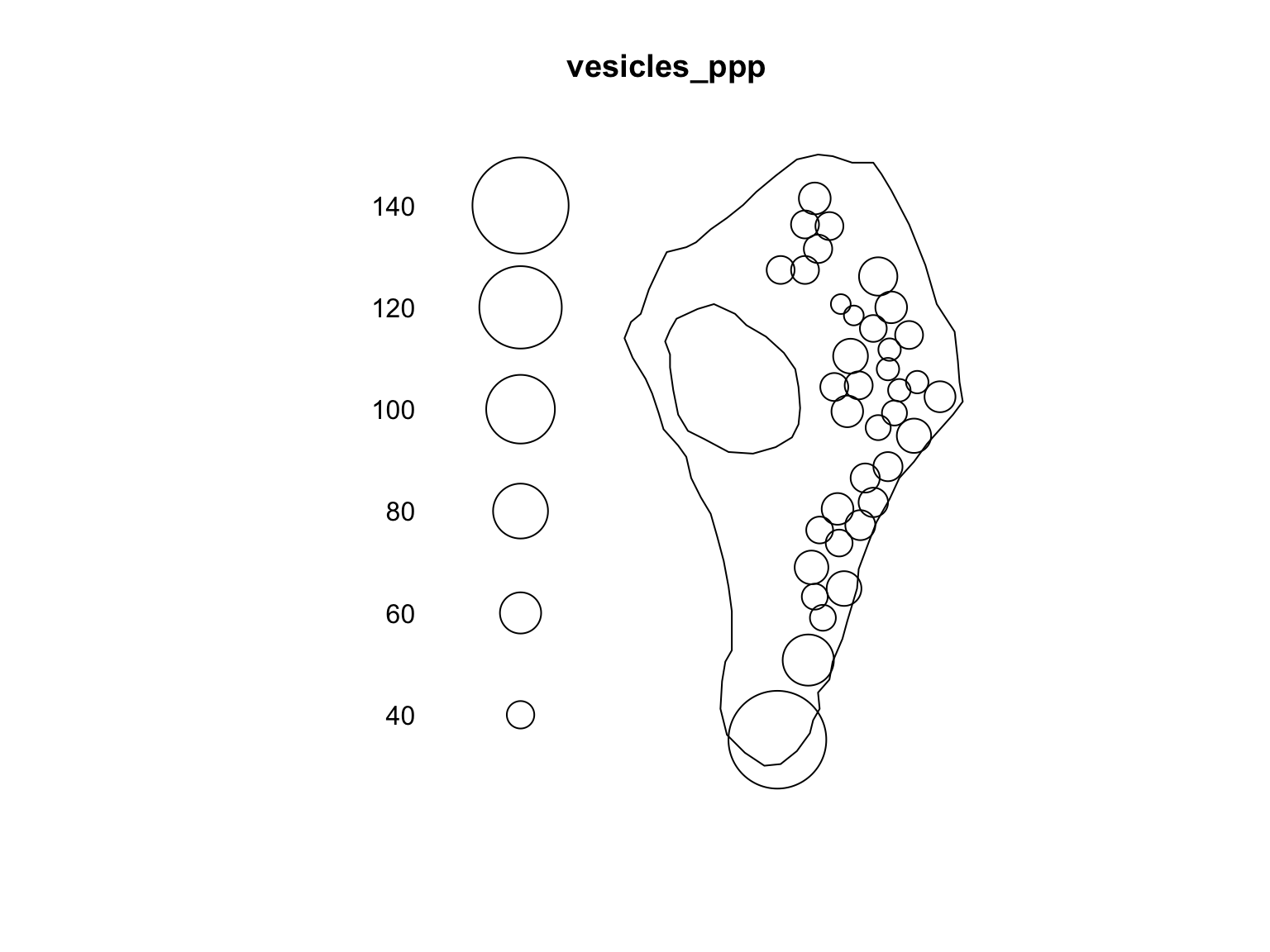

For example, we can use the nndist function to compute the

distance from each point to its nearest neighbour. We can then visualise

our point pattern based on this additional information.

#Store the marks

m <- marks(vesicles_ppp)

m$Dist <- nndist(vesicles_ppp)

marks(vesicles_ppp) <- m

head(marks(vesicles_ppp))## Group Size Dist

## 1 Inactive 0.0687878 46.13896

## 2 Active 0.5178509 55.85516

## 3 Inactive 0.2893958 40.73081

## 4 Active 0.1160360 40.73081

## 5 Active 0.1408090 46.29779

## 6 Inactive 0.5503479 41.35679plot(vesicles_ppp, which.marks = "Dist")

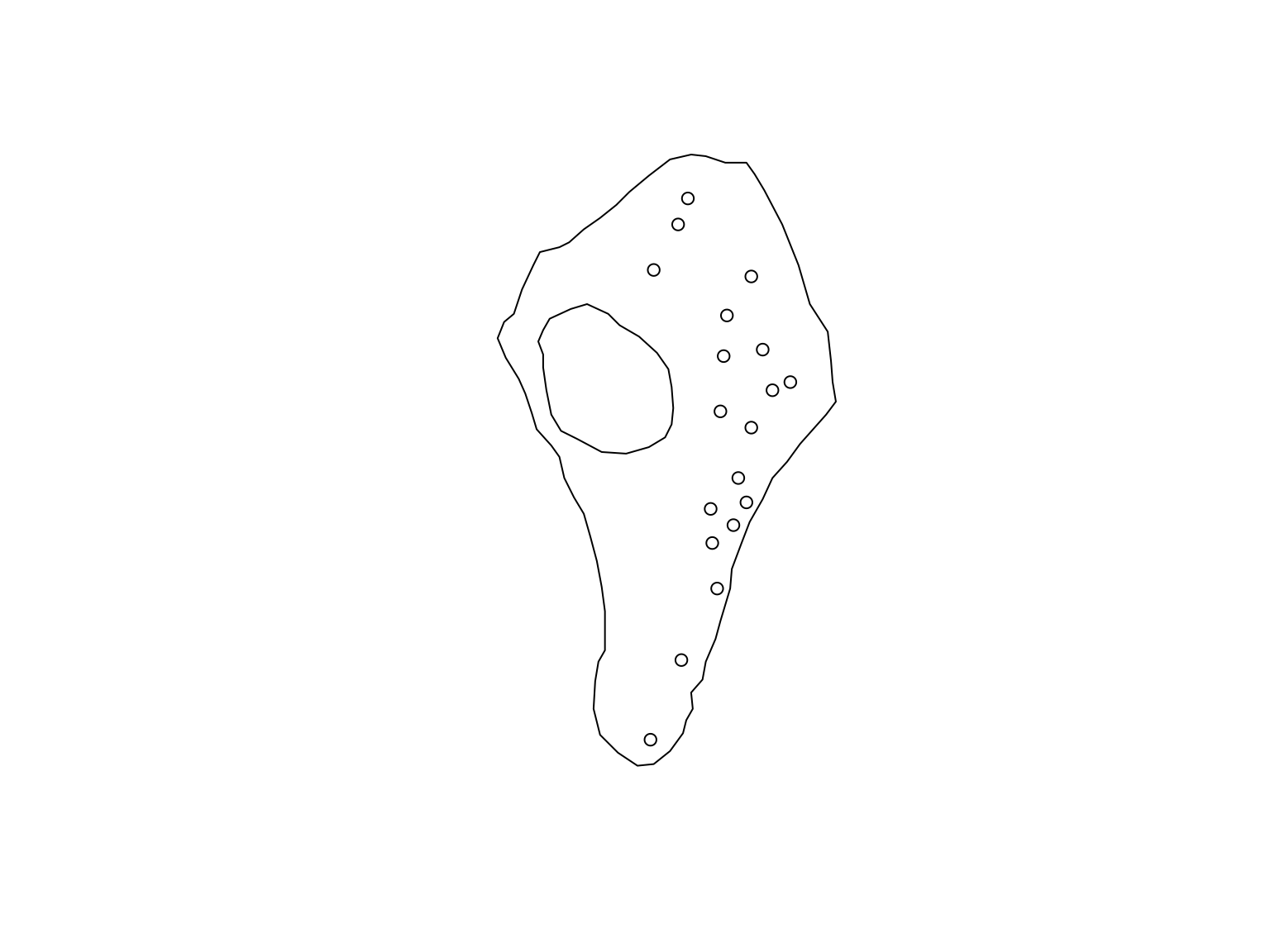

Point patterns can be subset using normal R data

wrangling methods like the subset function, or conditional

statements. For example, we might be interested in performing our

analyses on the points from the “active” group alone.

#Store the marks

m <- marks(vesicles_ppp)

m$Dist <- nndist(vesicles_ppp)

#Choose points from the "active" group

active_ves <- vesicles_ppp[marks(vesicles_ppp)[1] == "Active"]

plot(active_ves, use.marks = FALSE, main = "")

Working with images

The values contained within images can also be extracted or modified

as needed. One of the easiest ways is to use the subset index operator

[]. For example, if we are interested in identifying the

values of an ‘image’ covariate at the locations where points were

recorded we could do this as follows:

#Elevation at tree locations

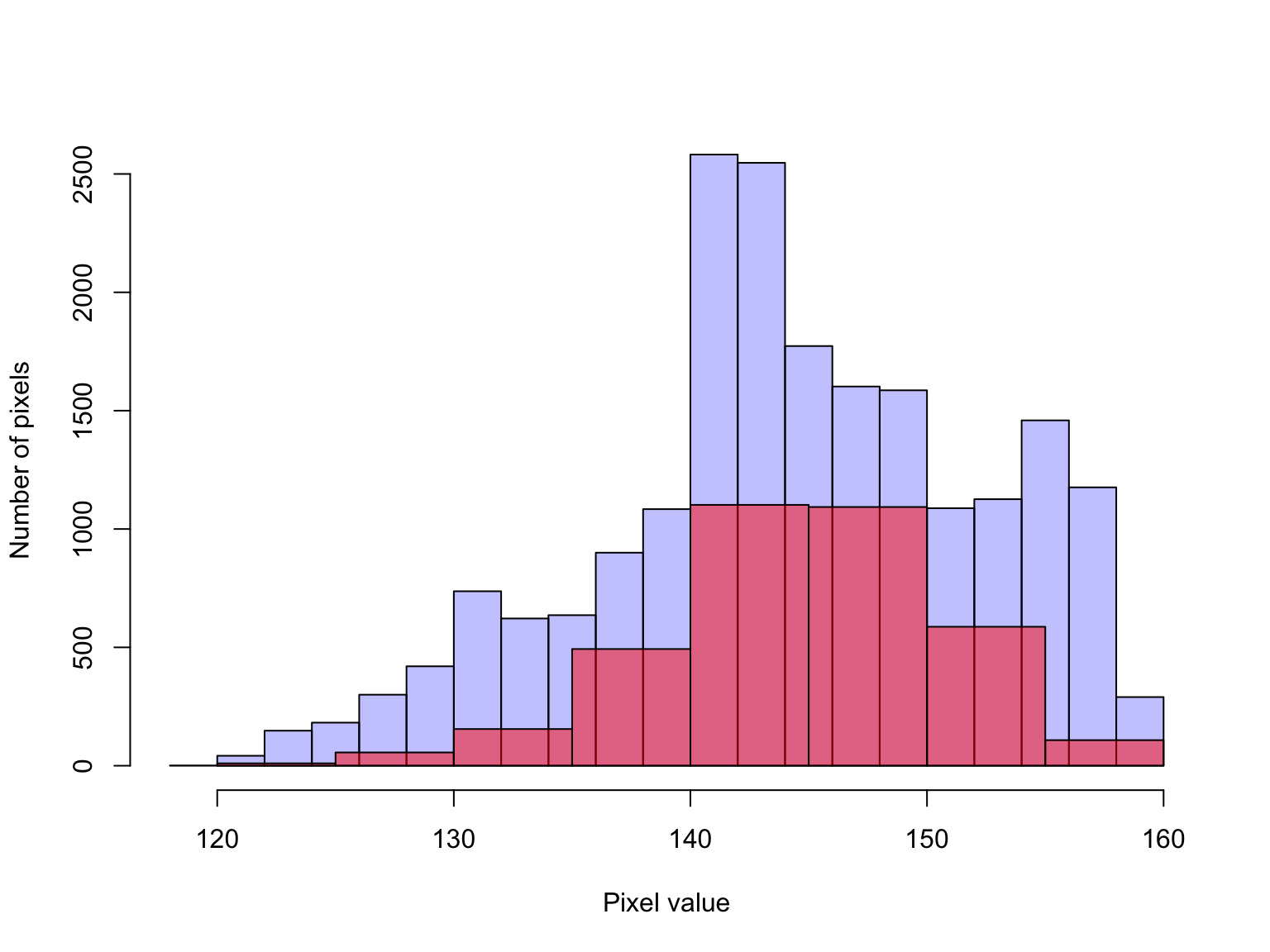

head(bei.extra$elev[bei])## [1] 138.32 129.64 135.69 135.86 139.53 139.87Similarly, a histogram of the elevation at tree locations compared to the elevation across the sampling window is a useful way to visualise whether there is any indication of a non-random spatial distribution of trees.

# histogram of elevations at tree locations overlayed on top of a

# histogram of elevations within the window

hist(bei.extra$elev,col=rgb(0,0,1,1/4), main = "") #blue

hist(bei.extra$elev[bei], col=rgb(1,0,0,1/2), add = T) # red

A full list of all of the functions that can be applied to

spatstat objects is provided in chapter 4 of Baddeley,

Rubak, & Turner (2015).

References

Baddeley, A., Rubak, E. & Turner, R. (2015). Spatial point patterns: methodology and applications with R. CRC press.

Khanmohammadi, M., Waagepetersen, R., Nava, N., Nyengaard, J.R. and Sporring, J. (2014) Analysing the distribution of synaptic vesicles using a spatial point process model. 5th ACM Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology and Health Informatics, Newport Beach, CA, USA, September 2014.